The Hidden Purpose of Customer Relationships

Why Business Tech Needs People

This is Part 4 in a blog series on Customer Relationship Marketing.

Part 1: Who is the Customer in Business Marketing?

Part 2: Orchestrating Three Pathways into Business Customers

Part 3: Key Customer Relationships for Tech Offerings

While the acronym CRM stands for customer relationship marketing, it lost the claim on the subject a long time ago. Today, CRM refers to the software for storing, retrieving, and managing your customer database overlaid with as many customer interactions with which we can get away from as much data we can muster. With due apologies to large CRM vendors who would want it to be otherwise, the idea of a business having relationships with customers is first and foremost a social idea of how a company's employees interact with customers. How businesses can market to customers to build, scale and manage such relationships is a special case of this social foundation of relationships. This has been true for decades for the B2B technology products, though we have now reduced customer relationship marketing to functional software to be purchased and implemented.

In this post, I explore the basis of relationships between a B2B tech company and its business customers. Relationships between business employees and their customers have a self-evident purpose based on the following functions: marketing to attract, sales to sell, and support to resolve issues. These functional competencies are well understood in tech over time, and each industry deals with these functional relationship challenges, good or bad. For example, telephone companies deal with customer support challenges, the auto industry with sales, pharmaceutical companies with marketing.

Beyond these functional relationships, I propose that social connections built between the company’s employees and customer’s employees are the prerequisites for B2B technology companies to build relationship marketing.

In a future post, I shall explore these patterns of customer marketing, which I define as the process of building, nurturing, and advocating the value created and exchanged between the customer and the tech company in the public arena to the mutual benefit of each side.

Since customer marketing requires this social foundation of customer relationships to be in place, we need to begin with a deeper understanding of what drives these relationships before public advocacy can be achieved.

Two Lenses on Customer Relationships

Functional and Social

Typically, relationships between tech companies and their business customers are viewed from a functional perspective. Often tech CEOs and their commercial teams assume that a functional view is all you need to win tech deals. For example, they might say, “We need sales reps to explain the tech benefits to close the deal.” Over time, they view the need “to scale” by replacing as many of such functional relationships through self-service, automation, or channels. All this may be true and necessary; however, there is also a social lens to relationships that serves a different purpose and can either prevent or accelerate adoption of technology products. The social lens explains why business tech products, in most cases, need people who play a deeper role than expected by their functions.

First, let’s review the two lenses:

The Functional-Business Lens

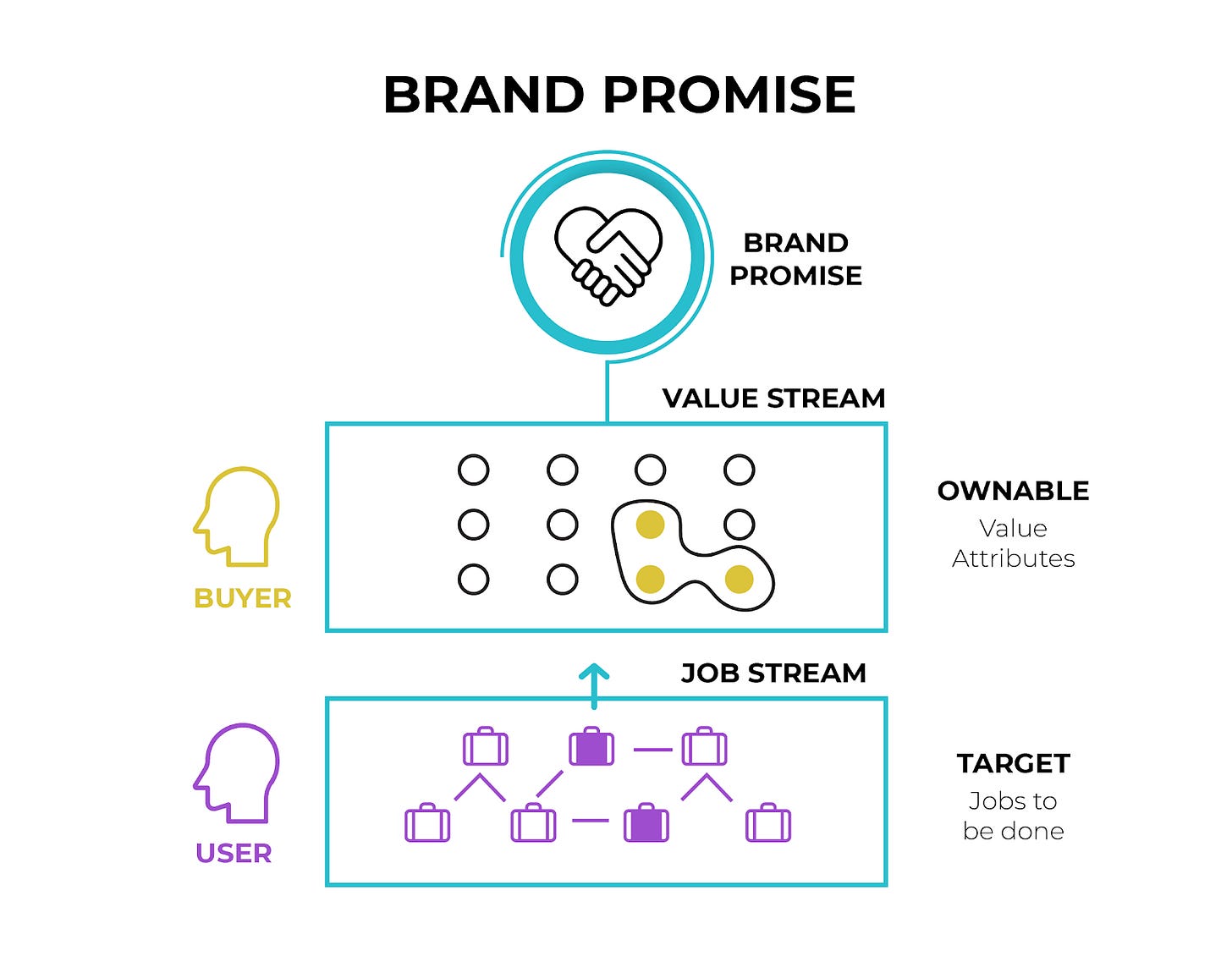

Most tech companies have something new and different to sell. So, their functional-business view is essentially a story that lays out what the tech brand has to offer to a business customer. In the best case, this can be a coherent brand story that addresses the questions: What promise can we make to our customers? What’s our unique insight? And how does our offering address a business need? (covered in Elements of a Tech Brand Story). Over the customer lifecycle, the brand promise and the story acts as the basis for marketing, sales, service and support teams to build specific relationships among the customers to deliver on the promise; that is, the promise helps communicate business value to the buyer and showcases the job for the user. A brand promise is the functional basis of a customer relationship. This view is summarized below.

The Social-Personal Lens

The social-personal view of customer relationships asks the question: Why should the customer trust the tech story or the promise? This view offers an answer based on personal relationships between customer and tech employees, from front-line support to executives. In this view, social interactions among key people between the tech company and the customer are needed to build trust in the tech products and their value.

This social-personal lens is very different for consumer tech products because the relationships for consumer tech products are typically not mediated through people. Think of the consumer trust in Spotify, Instagram, or Gmail. While it can be expressed in emotional terms, the basis for such consumer trust is mostly positive product experience delivered over time.

For B2B tech products, however, the social-personal lens is critical because certain key relationships are the basis of business growth (see Key Customer Relationships for Tech Offerings). Therefore, B2B tech products need people who can form the customer relationships that build trust in technology’s story and its promise.

Even when business stories are centered in emotional insights of the users or buyers, they are too broad and categorical (For example, buyers may value a faster business process from a tech). They need to be made specific for an individual business customer, and that happens through the quality of relationships between the people of the two companies.

So, let’s turn to the question: What is the social foundation of quality customer relationships?

Social Lens: The Foundation of Quality Relationships

Social Exchange

According to social exchange theory, the professional relationship between an employee of a tech company (sales) and the customer (buyer) is built on a series of exchanges that happen over time. These can be viewed as entitlements that a salesperson offers, such as product information, industry insights or competitive viewpoints that the customer values, making them indebted with gratitude. These exchanges over the course of time and combined with personal interactions (such as thank you notes, social gifts, and shared interests) become the basis of quid pro quo.

Building Trust & Commitment

Social norms around such exchanges vary. In many industries (such as pharma and government) and cultures, such quid-pro-quo exchanges are appropriately seen in bad faith with potential for conflict of interest. However, when suitable norms and guardrails are in place, these relationships build the social capital between the tech company and the customer. These exchanges are the bedrock of relationship quality building trust and commitment between the two parties. For complex solutions that need to be assessed, purchased, and deployed over a long time period, this confidence in relationships and desire to maintain them through the technology adoption process is needed by both parties.

Enabling Shared Risks and Rewards

This social capital built over time allows both parties to take risks and share rewards from the technology. The idea of shared business risk between the customer and the technology provider is very important. For example, how do both parties resolve conflicts that arise from new business terms for a technology? How do they manage setbacks during tech deployments? How do they negotiate the technology’s fair use? How these risks are managed by teams can either fuel or deplete the social capital. A strong trust and commitment foundation can allow such risks to be shared and navigated. On top of that, the customer and tech company can reap shared rewards—both individually (for example, the sales representative getting a bonus or the customer champion gets promoted) and collectively (for example, the tech company getting funding and awards or the customer growing in market share).

Creating the Foundation of Quality Relationships

In summary, there is social capital created by the ongoing social exchange between tech companies and customers, which allows both parties to manage the shared risks and rewards of adopting a new technology. This social capital needs to be built across all the key one-on-one relationships among the teams.

It is common for a tech company executive to have a direct relationship with a customer executive who sponsors the technology, a sales person to have a texting relationship with the buyer, the product managers know the tech users directly, and the support team to know the IT group. All these relationships come into play over the lifecycle of a B2B tech product adoption.

The Purpose of Customer Relationships in Business Tech

Such high-quality relationships are a social asset and can be used for many purposes, both functional and personal. Some of these purposes may even be unethical or dubious (for example, collusion, bribery, conflict of interest, and government contracts). I am not interested in such illegitimate uses in this post. The question I am interested in is:

What is special about business tech products that require high quality social relationships for their success?

All Major Tech Disrupts Business

There is indeed a common need across all business tech companies. They need to manage business disruption caused by the technology. The more potent the technology, the more disruptive it is to business. From mobile devices to cloud-based apps of the last decade to recent algorithmic or crypto innovations, every one of these technologies disrupts how a business operates.

To manage the disruption created by their tech products, tech companies need to build and sustain quality relationships with their business customers. This is different from consumer tech companies, which rely on consumers to navigate the tech change on their own.

Fundamentally, there are three kinds of business disruptions that need to be managed.

For Users: As the user becomes adept at a tech product (such as Slack), their job changes over time due to the very use of technology. A new technology progresses the job to be done. This job progression can be disruptive and require user training, support, and sometimes even removing the users from the workflow through job automation or elimination. Most business SaaS applications focused on operational workflows (such as accounting, expenses, sales, and support) fall in this category.

For Buyers: As the tech begins to create new value for the organization, the buyer may find that they need to reorganize the value chain and team structures supporting the work. This organizational change can be disruptive, requiring entirely new ways of organizing skills and labor. AI-based applications such as autonomous fault detection in the energy sector or algorithmic stock trading in finance drive automated actions by removing humans from the loop and end up restructuring the value chain.

For Network/Marketplace: As a new technology reorganizes jobs and teams, it may open up new pathways and channels to access users. Crypto technologies and robotic and satellite networks are a few examples of where entire ecosystems are being disrupted. In software, developer-led technologies are examples of new infrastructures and tools that redefine a new way to build apps and solutions (for example, DeFi apps on Ethereum blockchain) and spawn new ecosystems.

Customer Relationships are to Manage Tech Change

Not all technologies are equally disruptive. The deeper the technology (for example, cryptocurrency with blockchain and quantum computing), more likely it is to rewire the business at all three levels: the user, the buyer, and the network. However, it is important to realize that each of these disruptions needs to be managed differently depending on the quality of relationships between specific stakeholders.

For Users: As the user becomes adept at a tech product (such as Slack), their job evolves as well. This job progression slowly demands a new kind of work—one resulting from extended use of the technology itself.

In fact, the dirty secret of all business software is that each software category evolves to have a group of power users who wrangle the software for all other users or beneficiaries. From Acrobat to Marketo to Salesforce to Zoom, business software forces job specialization for a few users and job liberation (in fact, redefinition) for the rest.

Socially, this job change is navigated between users and software product managers. The product managers drive the relationship with the power users who determine product roadmap and adoption more often than light users. As the technology matures over time, the task of user acquisition and the relationship with light users is owned by growth marketers. Product-led growth depends on this division of labor and these key relationships.

For Buyers: As software starts changing the jobs being done by the users, the organizational structure starts changing as well. Buyers who care mostly about the value created also begin to care about new processes forced by technology. Often, organizational changes slow down or block the potential value created by technology. For example, robotic process automation (RPA) is a technology where human teams and processes have been substituted with automated bots affecting thousands of jobs and processes.

Therefore, technology vendor sales, service, and partner teams need to recognize and offer guidance to business customers in managing this disruption. The “best practices'' of digital transformation mostly consist of large tech service companies helping businesses manage wholesale organization changes.

Across company boards and management teams, technology is mostly evaluated from a buyer’s perspective (the economic impact, value chain, and workforce disruption) and less from the user perspective (changes to job scope). That is why B2B tech executives (especially in sales and services) need to have relationships at customer C-suite levels: to manage change.

For Partners: For technologies that either disintermediate existing routes to market or open up new channels, partner relationships take on importance similar to that of customer relationships. They offer access to users and buyers in a new way.

Why Change Triggered by Tech Can’t be Managed Through Tech

It may seem odd that disruptive tech requires human relationships to navigate in a business environment. Why can’t changes triggered by new tech be managed through the tech itself? There are many reasons for this, but the deepest is that the culture changes much slower than tech.

Specifically in a business, changes to jobs, organizations, and channels are mediated through people. Triggered by a product, the change management needed in skills, jobs, and resources takes a lot longer than the time it takes to deploy the product.

In fact, the deeper the tech, more it needs to be mediated through people in business. AI is a good example. While we have several AI models and predictions available in the health, finance, and insurance industries, many of the use cases have not yet been vetted to be socially acceptable because of regulation, privacy, bias, or other concerns. Similarly, cloud adoption in industries is often hampered by tech guardians who limit the growth of technology—for legitimate reasons.

Ultimately, human relationships are needed in most stages of the business to manage the change wrought by the technology. That may be the hidden purpose of all customer relationships in business tech.

Key Takeaways

In B2B tech, there are two lenses on customer relationships: functional and social. The functional lens asks the question: What is the technology promise? This is the brand promise made and kept by customer sales, marketing and support teams over time.

The social lens asks the question: Why should the customer trust this promise? Besides the product capabilities, the answer to this depends on the foundation of relationships that exist between the customer and the technology provider.

Social Exchange Theory describes how two parties can build relationships of trust and commitment through the reciprocal exchange of entitlements and gratitude over time.

Social Exchange Theory is especially critical in business tech because this allows customers and tech providers to share both risks and rewards over time that are inherent in most technologies.

By capturing shared rewards and mitigating shared risks, customers and tech vendors can form a foundation of quality relationships across a spectrum of stakeholders—from executives to buyers to users.

Such relationships are needed over time since virtually all major technology disrupts business processes, jobs, organizational structures and even ecosystems over time.

In fact, such customer relationships allow these tech disruptions to be managed between various parties. Absent these relationships, customers can struggle to adopt the full value of technologies in business settings.

Tech disruptions cannot be managed by tech alone, since people changes take longer than tech changes. Therefore, managing change may be the most common purpose shared across all relationships in business tech.

References

Marketing Strategy, Palmatier and Sridhar

Jobs To Be Done; Competing Against Luck, Clayton Christensen; JTBD - Anthony Ulwick

Michael Porter, Value Chain

This is Part 4 in a blog series on Customer Relationship Marketing.

Part 1: Key Customer Relationships for Tech Offerings

Part 2: Orchestrating Three Pathways into Business Customers

Part 3: Who is the Customer in Business Marketing?