This long post is inspired by a few ideas and books about human insight, psychology and behavior that I’ve returned to a few times. Each set of ideas offers an interesting framework which I've applied to the topic of how to attract customers. This interpretation is mine, even if the original ideas are from different domains. The books and authors are listed at the end of the post.

“Marketing is the social process by which individuals and groups obtain what they need and want through creating and exchanging products and value with others.” Peter Drucker

There are only two ways to attract customers.

One, to have them want your product.

Two, to have them need your product.

The first way is based on evoking desire among customers.

The second way is based on persuading customers.

Most businesses use both ways to attract customers.

Even if used together, each way is different in how it affects a customer.

So, each way represents a different type of attraction game.

An attraction game includes all tactics that pull customers through their journey, over time: from branding, promotion, sales to training, renewal and support.

Let’s call these two types of attraction games:

Desire Games and Persuasion Games.

Desire games evoke desire for what's missing in your customers’ lives without your product.

Persuasion games persuade them of what’s possible in their lives with your product.

Desire games create motivation, e.g. fear of missing out.

Persuasion games drive action, e.g. an offer.

Desire games help customers aspire to a vision.

Persuasion games help a customer progress towards it.

Desire games are social.

Persuasion games are rhetorical.

Desire games speak to a person’s subconscious mind.

Persuasion games speak to their conscious mind.

Game Purpose

The initial purpose of each game is to attract a customer.

The ultimate purpose of each game is to keep the customer.

Both games attract and retain customers over time.

But in different ways.

Desire games sustain the want.

Persuasion games deliver on the need.

Game Models

Each game has a different underlying model of human dynamics.

Desire games are based on evoking mimetic desire among customers.

“I Want It, Because Others Want It”

Mimetic or imitation-based desire is rooted in social insight: humans don’t desire things independently and autonomously, they desire things socially–they desire things because other people want them, too. [Rene Girard]

Persuasion games are based on motivating action among customers through rhetoric.

“I Need It, Because I’m Convinced of It”

Rhetoric is the skillful and combined use of logic (logos), credibility (ethos), and shared values (ethos) to convince others. [Aristotle]

Game Engines

Social media platforms serve as desire game engines.

They turn attention into new wants.

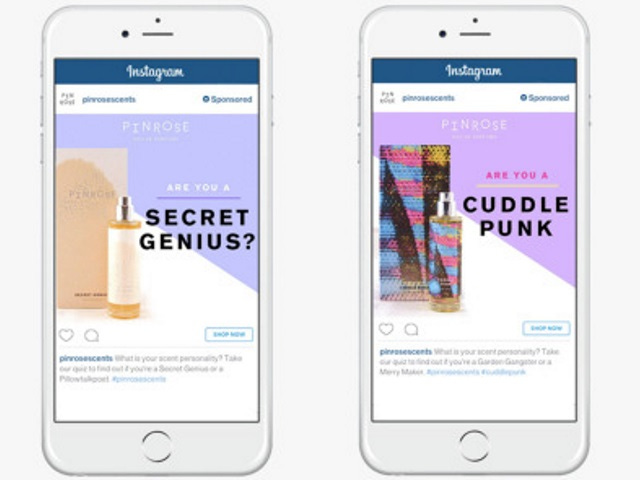

Consumer brands in entertainment, fashion, apparel, travel and food advertise on Facebook, Instagram and TikTok to build desire. Business brands use LinkedIn to build prestige to attract talent.

Search, e-commerce and marketplace platforms serve as persuasion game engines.

They turn intent into fulfilled needs.

Consumer brands use Google paid ads, Amazon marketplace to fulfill consumer needs (purchases). Business brands have industry specific B2B marketplaces for customer fulfillment.

Game Plays

Customers may not be aware that they are part of a desire or persuasion game.

If they become aware, they may opt out or limit their role in the games. For instance, many consumers limit their social media consumption to control their wants, or give up loyalty cards to limit their shopping.

Most customers, however, continue to participate in the games. They may do so consciously or for reasons hidden even to them.

Desire games are harder to detect, limit or opt out of than persuasion games. That is because we hide certain desires and motivations even from ourselves.

Desires are not bad, per se. There are two types of desires: thin desires that drive destructive cycles of seeking what others have; and thick desires that drive creative cycles based on our values that fulfill us over time. [Wanting, by Luke Burgis].

In desire games, often the product is only a small part of the fulfillment of desire. The want is stronger than the product or its experience.

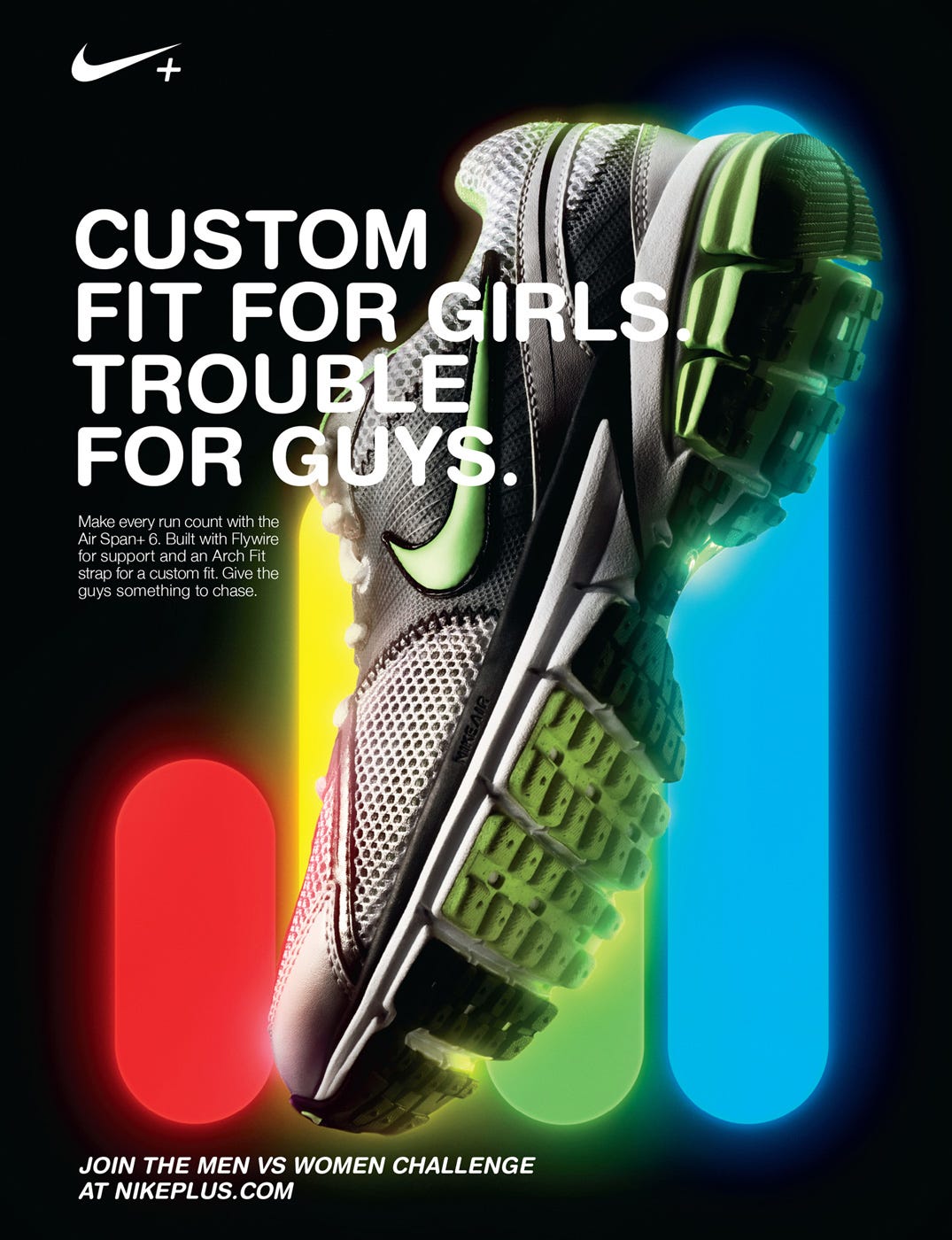

Therefore, strong consumer brands survive beyond their product life cycles and limitations. Example: Nike, Harley Davidson, Porsche, Coke.

Over time, desire games make their products symbolic.

If these top brands were to disappear, their customers’ desire would be thwarted, but they could fulfill their need for a shoe, bike, car or soda drink elsewhere.

Persuasion games are more common, especially in the business world, though they are not necessarily easier to build or play. This is because rhetorical skills may be easier to detect but are hard to resist or deflect.

Businesses use a mix of time tested rhetorical capabilities towards customers for this game, such as building reasoned value propositions, creating trusted relationships, signaling credibility and evoking shared values, and so on.

Businesses that are excellent at building need-based products are likely to excel at persuasion games.

Amazon is an ideal example of this with their obsession on fulfilling customer’s daily needs, from discovery to same day delivery. Google paid ads are another example fulfilling our daily information needs from searching to finding critical services.

Technology is fickle in creating desire. While many users are attracted by novelty, this is mostly variety seeking behavior, similar to trying a new food flavor. Most technologies do not last beyond the novelty stage. Therefore, tech companies with novel products often end up playing persuasion games.

Over time, persuasion games make their products utilities.

That’s why most tech products become obsolete once their utility is no longer needed, or get subsumed within other products serving similar or higher utility. If Amazon were to disappear, its customers would not be able to fulfill their needs, but they would not long for it.

Top Players: Apple and Tesla

While every business plays both games, most excel at only one of them. But, in this generation, there are two brands that have mastered both the desire and persuasion games: Apple and Tesla.

Both companies have built novel tech products (phones and electric cars) that millions covet; and they have also convinced millions of their needs. This is no small feat. To do so, each of them have built their own desire and persuasion game engines.

Apple has built an symbolic brand that evokes desire, controls its product experience (from apps, devices to chips), owns an app ecosystem and runs direct retail and ecommerce channels.

Tesla has built a symbolic brand with virtually no advertising, controls its product experience (from software to batteries and factories), owns its sales and configuration platform, and runs a direct showroom and services network.

Attraction Games: Influence, Morality and Society

Game Influence Levers

There are many levers to psychologically influence customers during the attraction games. The seven most common levers are: social proof, liking, scarcity, reciprocation, consistency and commitment, authority and unity. [Influence, by Robert Cialdini].

While all of them can be used in both the games, some levers are better suited to one game over the other.

Desire games use sociable and shareable levers of influence.

Social proof: The social proof of other “customers like you” using a product is a strong motivator for you to do so. For business customers, public references from other similar customers are credible evidence of the value of a product or service. In fact, private back-channel endorsements are perhaps the most powerful social proof of a product, or even a person.

Liking: Social media influencers build desire among their followers through likes. In business situations, the likeability of a sales person is a major factor in customers wanting to work with a business.

Scarcity: Flash sales and limited editions create consumer want through scarcity, real or perceived. In business, pre-orders, backlogs and time-bound offers can create a sense of desire through perceived scarcity of the product.

Unity: Often, brands signal their unity with consumer’s beliefs and identities to build a connection with them. It is a powerful but tricky tactic since consumers may question whether such signaling is real or performative.

Persuasion games use relational and personal levers of influence.

Consistency & commitment: To build trust, businesses need to steadily deliver on their commitments over time. This is the foundation tactic of all persuasion games. Promises made, promises kept.

Reciprocation: In business, sales builds relationships with customers through slow and steady increase of reciprocal exchanges and expectations. All consumer loyalty rewards depend on this tactic.

Authority: Expertise and credentialing can persuade customers even when other tactics are limited. So, most ventures begin with some form of authority, real or claimed, to persuade others.

Influencing Consumers versus Business

Companies attract both consumers and business customers with the desire and persuasion games, using all levers of sociable, relational and personal influence.

But how each game is played out in the public and private domains differs for consumers and business customers.

For CONSUMERS, companies like to play the desire games mostly in public, and persuasion games in private.

Desire Games: Social media influencers, brand ambassadors, endorsement celebrities - all model in public what the consumers should desire. Even scarcity tactics like flash sales, premium concert tickets, are mostly public. This is to achieve the largest number of followers who covet the brand.

Persuasion Games: Tactics like special offers, loyalty discounts are getting personalized and therefore more private for each consumer. This is to achieve the most effective way to convert each prospect into purchase.

For BUSINESSES, companies like to play persuasion games in public, and desire games in private.

Persuasion Game: To avoid collusion in the marketplace, companies need to make public as much as possible their product claims, value propositions and pricing. In competitive situations, companies need to deliver written bids and proposals to a business customer that are “public”, though confidential, within customer teams. As the buyers evaluate vendors, tactics like special offers, discounts are contractually reviewed and recorded. In short, a company needs to share their persuasive rhetoric within the customer organization for the buyers to make their purchase decisions and to defend them to the future auditors.

Desire Game: The personal desires of the business customers are often private, if not outright hidden. Customers covet a promotion, seek to attend an important conference, want to access influential business leaders, and generally raise their prestige among peers. In most cases, companies attract customers by offering to help them fulfill these desires. Tickets to sports games and concerts are given out in private. But all industries have legal and ethical limits to such private desire games.

Game Shortcomings

Each attraction game has its own structural shortcomings.

Desire games have social shortcomings.

As is evident from recent studies of social media, cycles of negative desire and addiction (“doom scrolling”) can generate consumer anxiety, FOMO and depression. In its extreme form, this desire can amplify group tribalism and scapegoat outsiders. Product fans can not just support their own cohorts but gleefully tear down competitors. From the Mac versus PC crowd of the last generation to the crypto crowd today [Bitcoin maximalists vs. others], strong communities can fall prey to internal divisions due to unwavering commitment to their group’s fervent desire. In business settings, companies can fulfill their customers' personal desires and gains through bribes or illegal quid-pro-quo.

Persuasion games have rhetorical shortcomings.

Persuasive stories fall apart over time due to cognitive biases and errors. The cognitive bias codex classifies four categories of such errors:

Dealing with too much information: results in biases to confirm our beliefs, to notice bizarre changes, find faults with others over self, etc.

Not finding enough meaning: creates fake patterns for conspiracy theories, stereotyping, etc.

Need to act fast: means we act with overconfidence and search for simple solutions, etc.

How we remember: results in misattributions, false memories and distorted recall.

Businesses use these shortcomings in their games wittingly or unwittingly.

And just as often, we fall for them on our own.

Either way, when we do we are furious about it.

Game Morality

As customers, we are all complicit in these games. We are eager to be seduced by the desire games, and ready to act from the persuasion games. We fool ourselves all the time - unwittingly or willingly.

Neither of these attraction games are inherently moral or immoral. Only the business’ intention and customer’s complicity determine the morality of each game.

Businesses may play the game poorly or unethically. Just as customers may be complicit explicitly or fool ourselves unknowingly.

While the immediate purpose of the games is to attract the customers, the deeper purpose is to deliver on the legitimate promise of the attraction. Every game that attracts a customer sets the expectation to fulfill their desire or need over time - in order to keep the customer.

In an ethical business, what the customer is attracted to (the promise) and what the customer experiences (the product) should be aligned.

This gap between promise to product may be trivial or profound. Yet the game’s legitimacy depends on this. Closer the product is to its promise, more likely the customers will consider the game legitimate - and more complicit they will be in the game.

If there is a significant gap between the promise and the product, customers see through the games as disingenuous or even fraudulent. We hate to be fooled by others.

Example: customers get mad when they see a corny ad for a beauty cream or meet a pushy used car sales person. “That’s just marketing or sales bullshit”. They don’t want to be complicit in these games.

Even when a business game is legitimate (such as social media apps like TikTok & Instagram), customers may become complicit in our failure. Doom scrolling is an example of where we fool ourselves.

Examples of games with huge gaps between their promise and product:

Game Choice & Control

The games can end naturally in one of two ways: either the business stops making the product or the customers stop seeking it.

Otherwise, stopping these games requires control, if not coercion, of either the business or its customers. Society sets controls on these games.

These controls may be legal (legislative, regulatory) or social (boycott, censure), etc. Examples: Laws against advertising cigarettes; parents preventing kids on social media.

The purpose of controlling the two games is different.

Desire games are controlled to limit the impact of the wants they generate.

Example: Cities are banning sweet, spicy and minty flavors of vapes because teenagers are more likely to be attracted to them. Governments are looking to regulate social media to limit its harmful effects on consumers' desires.

Persuasion games are controlled to limit the fulfillment of the needs.

Example: Pharma industry’s drug claims are closely regulated, and their sales tactics with doctors curtailed. Similarly, the advertising industry is restricted in how consumer’s sensitive information is captured and used.

For socially taboo categories (porn, drugs, alcohol), attraction games are entirely forbidden or controlled to limit both the desire and the means to fulfill them.

Ultimately, every society sets different norms for businesses to control their attraction games.

Games in Society at Large

So far, we have talked about attraction games in the business context.

What if the product is not a commercial offering, but a non-profit service (a religious charity), a government program (carbon tax policy), or even a social idea (universal basic income)?

Every day, various government, civic, media and nonprofit institutions bombard us with games to entice us to their ideas or even ideologies. Structurally, the two attraction games are still the same - make the citizens either want or need a specific policy, program or vision.

There is one categorical difference though.

In civic games, it is more common for others to fool us - and for us to fool ourselves. Unlike in commercial situations where feedback loops between customers and businesses can expose the game, civic games are more opaque.

In such games, the final purpose (the agenda) is often unclear to citizens or hidden from them, even when the initial stated purpose is clear. So, there is always a gap between the promise and outcome, between the ends and means. Often, what is proposed is not what is delivered. And therefore, citizens are eternally questioning and contesting these games.

Example: a non-profit may attract donors with a desire to reduce poverty, but the program impact may not be measurable for years. A tax policy may be persuasive initially, but its unintended consequence may not be visible for years.

Conversely, we may fool ourselves that we are supporting a non-profit for its cause while we may seek only our name on the donor list to signal wealth, generosity or compassion.

A Word of Caution

Though we may be enticed by these games, we should be vigilant that they are not weaponized against us.

Politicians seduce us to their visions of the future with desire games.

Bureaucrats convince us of their policies with persuasion games.

Big business does both to protect its vested interests.

Social activists and NGOs pursue their games with hidden motives.

Just like we would opt out from illegitimate business games, as customers; we should guard against games of false visions [wants] and rich promises [needs], as citizens. We should question our own willingness to identify with these games.

We should be careful of institutional intentions, and our complicity in these games. And if the games turn disingenuous or fraudulent, it is our civic duty to dissent, disengage or dissuade others from the power of these games.

REFERENCES

This post was inspired by the following books & their ideas.

Finite and Infinite Games

The main inspiration is the short but stunning book Finite & Infinite Games - James Carse.

"There are at least two kinds of games: finite and infinite. A finite game is played for the purpose of winning, an infinite game for the purpose of continuing the play.”

Mimetic Desires

Luke Burgis: Wanting: The Power of Mimetic Desire in Everyday Life

An excellent book on the ideas of Rene Gerard.

As discovered by Rene Gerard, the social insight is: humans don’t desire things independently and autonomously, they desire things socially–they desire things because other people want them, too. Mimetic Theory

Influence

A classic on how we get influenced.

Self Deception

The Elephant in the Brain: Hidden Motives in Everyday Life

“The main thesis of the book is that we are very often not aware of our real reasons for most of our behaviors. Our behaviors are optimized for living in a social group and very often, from the point of view of natural selection, it is useful if we are not consciously aware of our real motivations.”

Rhetoric and Biases

The Rhetorical Triangle: Understanding and Using Logos, Ethos, and Pathos