What is Customer Relationship Equity?

And how much should a tech business invest in it?

This is Part 6 in a blog series on Customer Relationship Marketing

Part 1: Who is the Customer in Business Marketing?

Part 2: Key Customer Relationships for Tech Offerings

Part 3: Orchestrating Three Pathways into Business Customers

Part 4: The Hidden Purpose of Customer Relationships

Part 5: Pursuing Business Growth with APIs

Most CEOs and entrepreneurs in business tech intuitively understand that inter-firm relationships between their company and their customers are critical—that the quality of their sales relations with buyers determines the deal outcome, that their customer support depends on how their service agents handle the escalations, and that their early product adoption may be limited by user relationships within their reach. All these are inter-firm practices where relationships between tech company employees and business customer employees directly affect the growth of the tech company.

Collectively, we can call this the customer relationship (CR) equity: the sum total of all the key inter-firm relationships between a tech company and its customers that determine the company’s growth.

In this post, I explore the main factors of CR equity and consider how much a tech business should invest in such relationships since all customer relationships are hard to establish, expensive to maintain, and difficult to grow.

The main question is how much should a tech company invest in people relationships?

As we address this question, we end up creating a customer relationship model for a tech company. This model establishes the scope of relationships necessary to a tech company's business model and then determines the specific relationships in which a company should invest for growth.

Let’s begin with the foundation.

Three Factors of Customer Relationship (CR) Equity

According to Palmier and Sridhar, there are three factors that contribute to such inter-firm relationships: quality, composition, and coverage. Together, these factors allow a company to understand the sum total of their relationships.

Relationship quality focuses on the specific nature of a relationship between two individuals at the respective firms and is a measure of depth of such a relationship.

Relationship composition is the mapping of various types of customer relationships according to the power they wield on the adoption of your technology inside an account.

Relationship coverage is the measure of the reach your technology has within a customer quartet (user and buyer types), within a customer account or segment, or within a network or marketplace.

Relationship Quality

In a previous blog post, I mapped out the four key customer relationships for any business tech company. These four relationships—the relationship between users and product managers, buyers and sales people, marketplace and partner managers, and IT services and IT enablers— are the most critical ones for a tech business. The foundation of social capital a tech company builds with its customers is built through each such relationship, one brick at a time.

In another post, I explored how this social capital is generated between the tech company and business customers through a series of social exchanges that build mutual trust and commitment. Over time, such trust between people allows the two companies to take shared risks and reap shared rewards. At its core, a deep foundation of such quality relationships between key employees allows tech companies to help customers navigate the business disruption caused by their new tech products.

This social capital is the first critical factor of CR equity. The measure of social capital captures the relationship quality, or depth, between two individuals across the firms.

A quintessential example of relationship quality is in the relationship between a startup CEO and the first few buyers. Very often, the CEO builds the social capital with each buyer during the sales cycle through references, shared connections, and face-to-face interactions and sets the terms for the first few pilots and the deals. This is especially true for high-value accounts. Similarly, the product manager of an early-stage company invests in building direct relationships with the few top power users to get feedback that cannot be obtained through transactional means like surveys.

For later-stage tech companies, sales teams carry most of the accountability for high-quality relationships with buyers. In fact, the biggest obstacle to growth in large accounts is the lack of high-quality relationships between the firms. This explains why the best enterprise sales people nurture and guard their buyer relationships closely. In many cases, the salesperson may even do so at the expense of the company. I have known top salespeople who have refused to sell a mediocre update to a product because they believe this will set back their buyer relationship. Conversely, one of the ways to drive growth in an enterprise is to bring in a salesperson “with a rolodex” who has standing high-quality relationships with buyers. These relationship tactics are not always effective on their own, but they speak to the primary role relationship quality plays in driving growth.

Relationship Composition

The second critical factor of inter-firm relationships is the composition of relationships between the tech company and the customer. Not all relationships are equal in power, even if they are equal in quality of trust and commitment between the two people. This is especially true for relationships surrounding technology products where we identified at least four different customer subtypes. We know that each member of this customer quartet (the user and the buyer from the business and tech domains, respectively) interacts with their tech company counterparts with a different purpose.

But do the users and buyers hold the same power in making technology decisions?

This is a tricky question because it depends on the growth pathways a company is pursuing. For a company pursuing product-led growth, users may have more power initially, whereas for account-driven growth, buyers may hold the relationship power.

In business sales, there are many conventional ways to assign power to various customer roles, such as “decision maker” or “approver.” These are situational and vary across companies and domains.

However, there is a deeper way to think of relationship power and the role of technology.

Fundamentally, most tech products are disruptive to a business. They change the status quo of how things get done. They alter jobs to be done, change workflows, introduce new practices, generate new data, and raise expectations of new outcomes. In short, most tech products drive change that makes people uncomfortable. That is why startups seek customers who are early adopters and believers.

Essentially, for a business tech company, the purpose of having power in a customer relationship is to drive the adoption of their technology in a firm. To do so, the company needs to identify the power wielded by each person in their customer base, in fact, by each person in an account that can influence technology use, purchase, or adoption.

In a complex sales cycle or during the critical stages of the technology deployment and usage, a company needs to understand who is for and against this adoption.

Each person’s power can be summed up on two axes: their capacity to drive change inside the company to adopt the technology and their attitude towards the company’s tech offering. This yields four relationship types.

A champion is a person who is positively inclined towards the tech product and can drive change. The kind of change may vary. For a senior buyer, this may be organisational change needed to manage disruption unleashed by the technology. In a large firm, a champion buyer can drive the change necessary to extract economic benefits from the technology. For champion users, the change may be to their work habits as the product simplifies or improves their job to be done. For critical developer tools, champion developers can make or break the tech usage inside a firm.

A blocker is a buyer or a user who is negatively inclined to the product and has the power to resist change in the company. This is especially true for technology guardians in a company whose job it is to protect the firm from harm. These guardians are not just in IT or corporate governance but also in business functions. Many valuable consumer technologies take years or decades to be adopted by businesses simply because there are powerful interests that block their adoption. These interests and the people who serve them are most often legitimate—a fact that many tech companies do not fully appreciate or understand. (For a deeper discussion on this topic, see the section on Technology Guardians and Limits to Growth.)

An influencer is a buyer or a user who is positively inclined to the product but has limited power to drive change. Often, tech companies make the mistake of building quality relationships only with influencers who have limited ability to effect change. Companies are later surprised when their sales or product adoption stalls inside the account. Marketing to influencers can be a valid pursuit, but a separate strategy for increasing reach or improving preference among champions and blockers is also needed.

A detractor is a person who has negative opinions on technology but can neither stop nor drive change in the company. A vast majority of buyers and users for a new tech may fall in this category. If that is the case for a tech company, it is important to ignore or limit relationship investment among detractors. If detractors have power outside of the company in the broad marketplace, then a company may need a targeted communications plan to limit their effect on the market—the inverse of influencer marketing.

Relationship Coverage

The third critical factor of relationship equity is relationship coverage, which is the measure of reach a tech company has among its customers. To measure coverage, a tech company can audit the number of relationships they have in all their routes to market. While these can be summed up in many ways, it is important to map the relationships in line with the business model.

The first category of relationships to audit are the direct ones between your employers and customers. For each business customer, these relationships form a quartet of business and tech users and buyers. Once mapped, these can be summed up across accounts, which in turn can be aggregated at the level of business segments (e.g. customer size, geography). Finally, for companies accessing customers through networks or the marketplace, they can identify and count the key partner relationships that determine access to such channels.

Companies that pursue product-led growth realize the importance of relationship coverage immediately. At an early stage, the tech product managers build close relationships with many power users to understand product usage. The coverage is limited to these user relationships. Slowly, they extend the reach to buyers to ensure that their product can be purchased centrally. Once this user adoption takes off, marketers expand their reach within an account or a customer segment to access new users and buyers. As these become saturated or if the product needs to be part of a community, companies turn to critical partner relationships to drive coverage of even more users. This sequence is simply an illustration of how relationship reach may expand. Each market may have a different path. For developer tools, the relationship path may be to first drive reach with a niche community of early developers, then build reach among power users with key companies, and finally get to tech buyers who support the rollout of new software tools inside the company.

We may need to define other ways to audit relationship coverage for more complex routes to the market, as in regulated industries (e.g. health, finance, and the public sector). However we do so, these three factors—depth, power and reach—are the components of a firm’s CR equity.

How Much Should A Tech Business Invest in CR Equity?

Building high-quality direct relationships, ensuring the right composition of such relationships, and achieving the coverage of such relationships in the market can be very expensive for a tech company. A good portion of the sales and marketing budget of a tech company can be directly attributed as an investment in CR equity. So, the critical question is how much should a tech company invest in business relationships?

Understanding the three factors is a good start, but none of these factors alone or together can tell us the scope of business relationships needed. By scope, we mean how much do relationships matter to a tech company’s business model? What is the intensity of relationships demanded by the tech company’s business model (relationship orientation) based on where the customers are in their journey with the tech company (relationship stage)?

Together, the relationship orientation and stage govern the scope of relationships warranted by a tech company. They describe the normative scope of equity a tech company should build in people relationships. Too little, and the business suffers; too much, and the effort is squandered.

First, let us look at a tech company’s relationship orientation—or intensity—towards business.

Establish Your Business Relationship Orientation

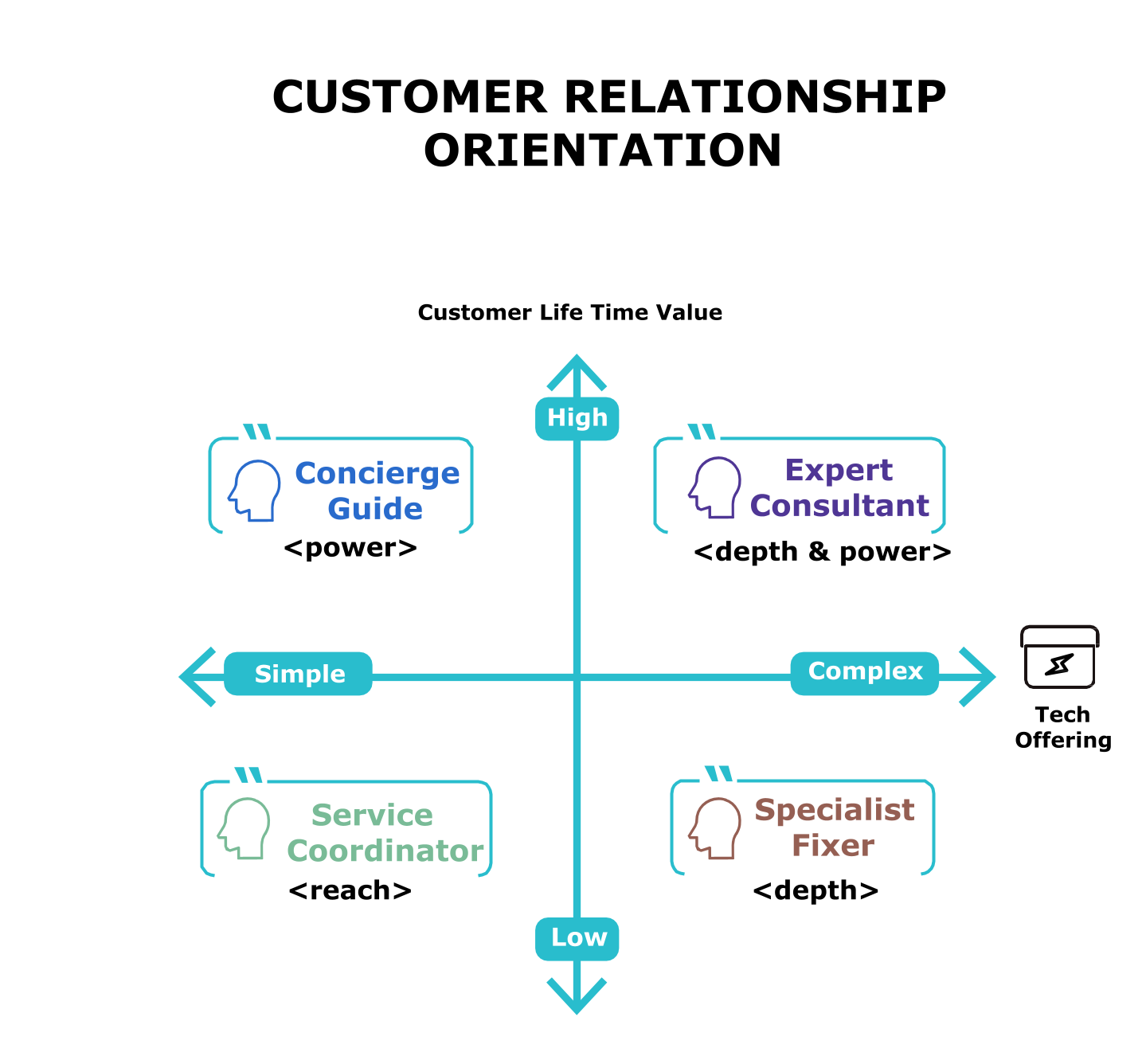

Each business has a different orientation towards customer relationships. Some need multiple high-touch, ongoing intense relationships within a customer account, while others need a few sporadic self-service, or low-touch, relationships or perhaps none at all. For a tech company, this orientation can be established based on where the company falls on two axes: customer lifetime value (LTV) and the nature of the tech offering.

The level of customer LTV limits how much is economically feasible for a company to invest in people, whereas the level of offering complexity determines how much is economically necessary to invest in people, in order to support technology evaluation, usage, and adoption among customers.

For each of these four quadrants, we can describe the orientation or intensity of relationship through an example persona taken from our personal lives.

“Expert Consultant”

A tech company selling high-priced, complex solutions to large accounts fits in this group when the product requires expertise to deploy, pricing is complex, and it takes time to deliver business value.

In such situations, the company needs to build a set of high-quality relationships in sales and customer service (depth) with the right composition (power) within an account with access to champions and influencers to achieve and sustain success.

Usually, such relationships between the tech company and the customer span quarters and years and are hard to dislodge by others.

Palantir is a good example today of such a company. Their data products require deep partnerships between customer engineering and privacy teams. Their relationship orientation is that of an “expert consultant.” In their own words: Palantir Foundry offers a range of data protection functionalities that have been developed in close partnership with our customers over the years and now enable them and others to comply with complex laws, such as the EU GDPR and the California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA). Such product complexity demands an “expert consultant” relationship with customers.

In our personal lives, an analogous relationship is the one we have with our financial advisor, who may know more about us than our friends and neighbors.

“Service Coordinator”

At the opposite end, tech companies with simple tech offerings and low customer LTV have the relationship orientation of a service coordinator. Such companies need to invest in minimal relationships, mostly to coordinate continued usage of products among the users. The key factor is to maintain relationship reach across as many customers as feasible through programmatic coordination.

Most developer tools fit in this category. Each tool is used for a specific purpose by a core set of users, often a team, to build a software artifact or solve a software problem. Initially these tools may be free and often have low LTV.

JFrog, a devops platform, is a recent example of this. While such tools can grow to be critical to a business (e.g. Stripe and Twilio), they begin with a developer community-focused, self-service relationship orientation offering great documentation, clear pricing, self-guided learning, and asynchronous support.

In our personal lives, this is similar to our relationship orientation with a fast food vendor or corner grocery store: self service and convenience trumps everything else.

“Specialist Fixer”

This relationship orientation applies to tech companies with high complexity of their tech offerings but low customer LTV. Such companies need to invest in short, credible relationships to ensure rapid product deployments to achieve success with minimal need for ongoing engagement. The key factor is relationship depth to get things done right once with occasional specialist support if needed.

Purpose-built specialist SaaS products in various complex categories like security and martech fit this characteristic. As the recent list of the top 27 marketing tech tools suggests, each tool category (e.g. web analytics, email optimisation, and social media management) has a specific purpose that requires an expert user to master the tool to solve a specific problem.

Hubspot is an example of a marketing tool that offers ongoing value to campaign marketers but requires expertise to customize for complex situations.

In our personal lives, this is similar to our relationship orientation with a plumber: we don’t need one often, but when we do, they better fix the problem.

“Concierge Guide”

Tech companies with simple tech offerings but with high customer LTV have this relationship orientation. Such companies need to invest in a few powerful relationships to ensure that customers continue to value their product long after it is deployed and in use. The key factor is access to a few powerful relationships to ensure ongoing championing of the technology within the customer.

Tech companies that offer AI and automation tools and applications fit this orientation. With multiple use cases, such products have a high LTV at a single account. UIPath and Automation Anywhere are companies in the fast-growing category of robotic process automation (RPA). They implement dozens of use cases in which rote steps of business operations (such as data entry) are replaced by programmable bots.

Their relationship orientation is based on their power to direct their customers through different use cases. The recent S1 of UI-Path confirms this method: they start small with a simple use case and then expand in a high-value account with additional use cases.

In our personal lives, this is similar to our relationship orientation with a hotel concierge: a few choice interactions can lead us to better experiences.

A tech company should establish the relationship orientation for their business early in the game. This sets the stage for how much to invest in relationships across all functions. Switching orientation is very hard for a company. Once investments have been made in people and processes to be a “service coordinator,” then becoming an “expert consultant” may take years—and vice versa.

Map Your Relationship Stage to Customer Journey

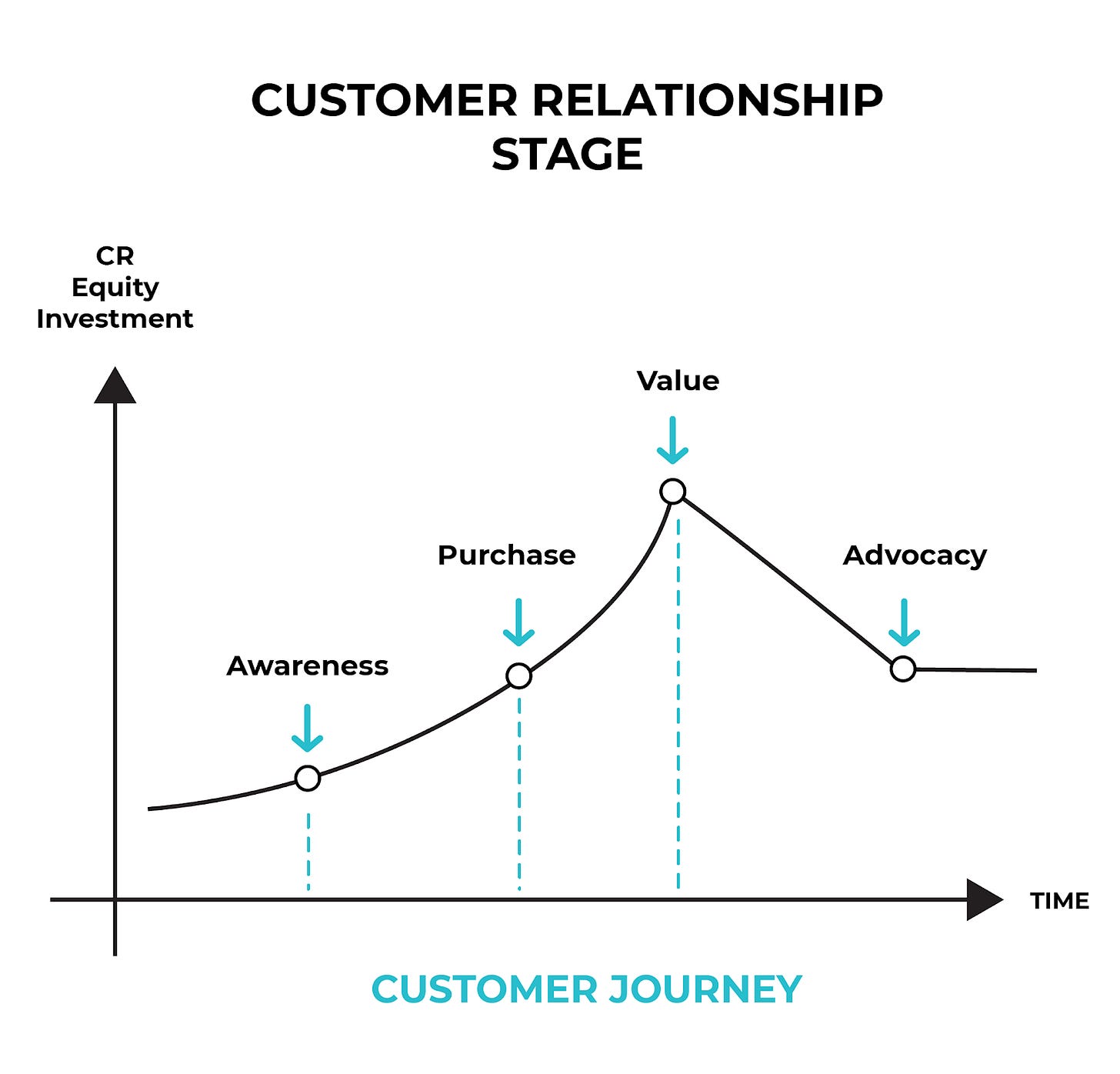

The second aspect of relationship scope depends on where the tech company is in its journey with the customer. Clearly, as customers move from becoming aware of the tech product, to purchasing it, to using and extracting value from it, to becoming a satisfied advocate for it, the company increases investment in relationships commensurate with each stage. Typically, the relationship investment increases slowly, becoming the highest when the customer realises the value from the product.

As an interesting aside, this relationship investment by stage mirrors the Brand Story and the Hero’s Journey.

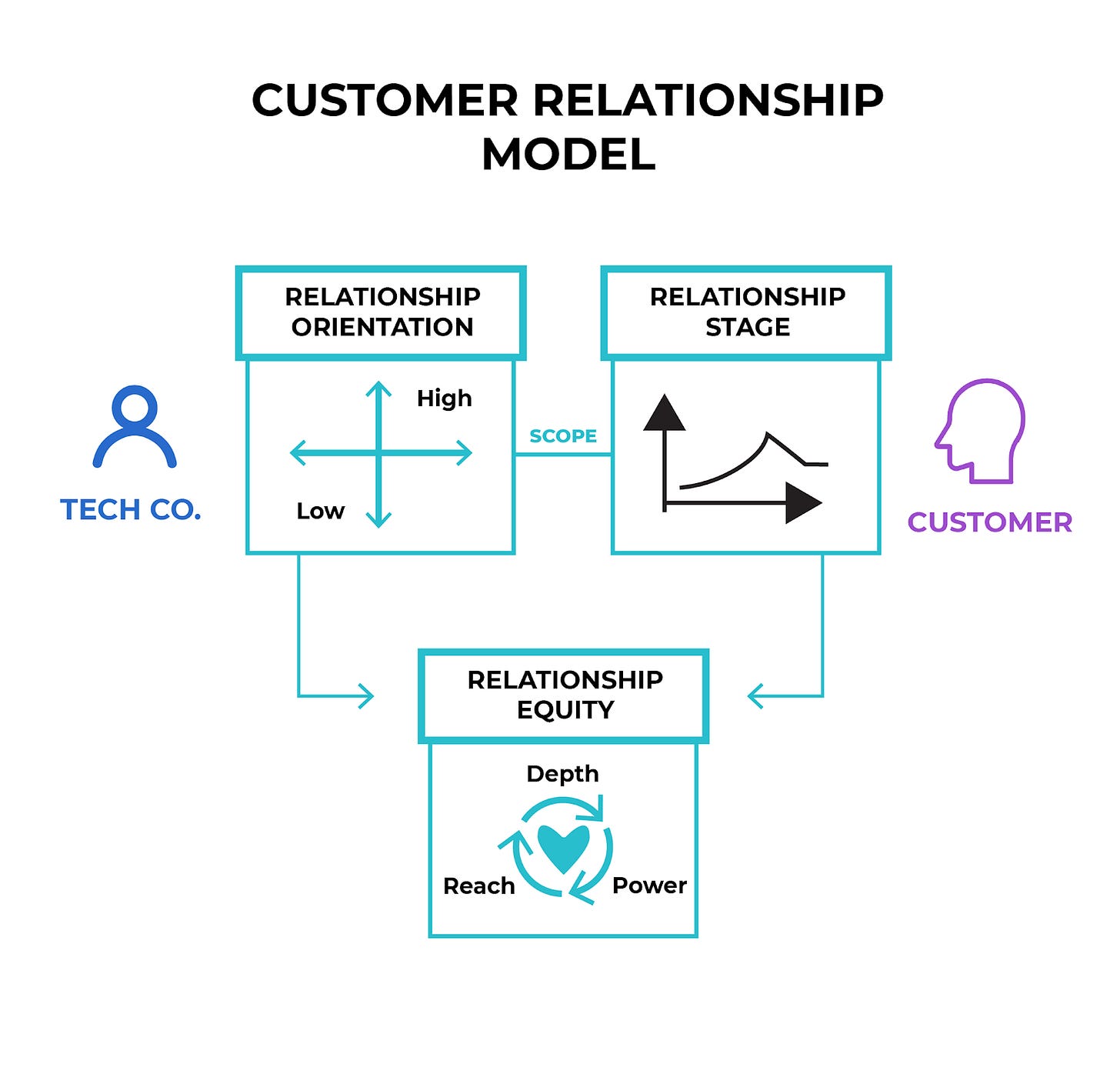

Your Customer Relationship (CR) Model

We can put these pieces together to now answer the question: how much should a tech company invest in relationships? Your customer relationship model determines the scope of relationships for your business model, which in turn establishes the customer relationship equity needed based on the three critical factors of relationship depth, power, and reach.

Now that we have all the elements of a customer relationship model, we can begin to ask the following questions: How should a tech company audit its existing relationships using this model? How do different relationship models drive different growth pathways? Where and when do we invest in relationship equity to achieve growth? Ultimately, what drives all relationship models? I shall turn to these questions in my next post.

Key Takeaways

Customer Relationship (CR) Equity is the sum total of all the inter-firm relationships between a tech company and its customers that determine the company’s growth.

CR Equity has three key factors: relationship quality, which measures depth; relationship composition, which measures power; and relationship coverage, which measures reach.

Social capital determines the depth of relationship quality between two individuals across the firms. It takes time to build this capital through trust and commitment.

The relationship power can be summed up based on a person’s capacity to drive change inside the company to adopt the technology and their attitude towards the company’s tech offering.

To measure relationship coverage, a tech company can audit the number of relationships they have in all their routes to market.

CR equity cannot tell us how much of it is needed for a business. For that, we need to determine the scope of relationships necessary for a business.

The scope is set by the intensity of relationships demanded by the tech company’s business model (relationship orientation) along with where the customers are in their journey with the tech company (relationship stage).

Putting this together creates a customer relationship model that sets the scope of relationships for your business model, which in turn establishes the customer relationship equity needed based on the three critical factors of relationship: depth, power, and reach.

References

AI Multiple: Top 67 RPA Usecases/Applications/Examples [2021]

Palantir: Business Model

Palmatier and Sridhar: Marketing Strategy

Stackshare: The Top 100+ Developer Tools 2019

This is Part 6 in a blog series on Customer Relationship Marketing

Part 1: Who is the Customer in Business Marketing?

Part 2: Key Customer Relationships for Tech Offerings

Part 3: Orchestrating Three Pathways into Business Customers

Part 4: The Hidden Purpose of Customer Relationships

Part 5: Pursuing Business Growth with APIs